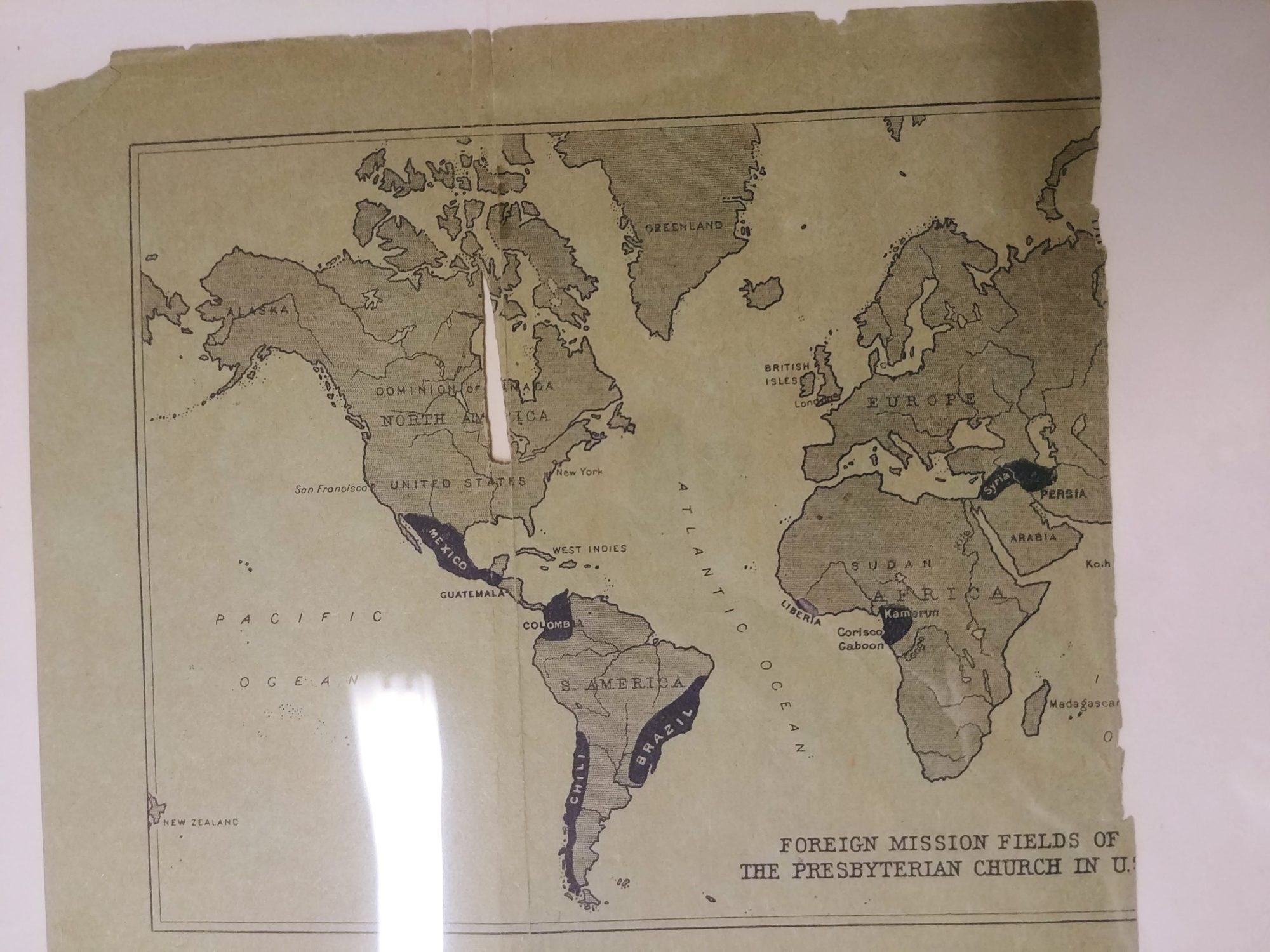

Early 20th century map of Presbyterian Mission Fields around the world. Original copy in Penn Museum Archives, Matthew Kerr Papers.

I recently attended Ira Dworkin’s talk about his book, “Congo Love Song: African American Culture and the Crisis of the Colonial State.” In the Q&A, I asked: How did Sheppard and Brown see their identity in relation to Africa and their responsibility to the continent before and after their missions?

The author said this is a great question and one of the hardest to answer.

In forming my question, I had been thinking about the late 19th and early 20th centuries, when William Sheppard and Althea Brown Edmiston (she went to the mission field with her maiden name and married while in the Congo) began their mission tours. I had been thinking about the rise of African American religious nationalism, about African Americans like Bishop Henry McNeal Tuner daring to state “we have as much right to think God is a Negro.” About the rise of Pan Africanism. About liberation theology in the antebellum and Reconstruction eras. About most Black people in the U.S. already being some 12 generations removed from Africa and determined to lead America into its promise of freedom yet still being able to conceive of a different ancestral homeland. About the atrocities being carried out in the Congo as black men, women, and children were lynched across the South. About seeing The Philadelphia Negro juxtaposed against Congolese people *purchased* by Europeans for display at the 1904 World’s Fair. About the respectability politics governing elite African American institutions and those institutions’ ongoing effort to tear down at home, in the U.S., the very stereotypes—savage, sexual deviance, uncivilized, lacking any culture—that imperialists were using to justify their imperialism. About the starring role conversion to Christianity was playing in the colonization project. About knowing that, on the one hand, Black Liberation Theology isn’t part of your denomination’s vernacular, but on the other hand, knowing Jesus Christ and wanting deeply to spread the gospel with compassion, service, and love.

Yes, I had been thinking about all that. And marveling at how complex it can be to be Black and Christian and woke, how complex it has always been. And how much more content I wish were available by the ancestors who navigated these questions centuries before I did.

Recent Comments